I film di questa sezione sono:

AUTOETNOGRAFIA

di Iván Reina Ortiz

Colombia - 2021 - 16 min.

(lingua: spagnolo / sottotitoli: inglese)

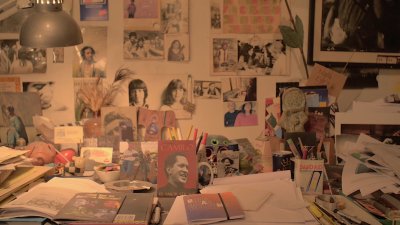

CAMILO TORRES RESTREPO, EL AMOR EFICAZ

di Marta Rodríguez, Fernando Restrepo

Colombia - 2022 - 71 min.

(lingua: spagnolo / sottotitoli: inglese)

EL LADRON DE MASCARAS

di Germán Ruiz Rivadeneira

Colombia - 2021 - 14 min.

(lingua: spagnolo / sottotitoli: inglese)

SEMILLAS AL VIENTO

di Mónica Borda Sáenz

Colombia - 2022 - 25 min.

(lingua: spagnolo / sottotitoli: italiano)

PASO A PAZO

di Luis Carlos Osorio Páez

Colombia / Italia - 2022 - 28 min.

(lingua: spagnolo / sottotitoli: italiano)

ABRIR MONTE

di Maria Rojas Arias

Colombia / Portogallo - 2021 - 25 min.

(lingua: spagnolo / sottotitoli: inglese)

NACIMOS BAILANDO

di Juan Diego Puerta López

Italia / Colombia - 2022 - 11 min.

(lingua: italiano)

Omaggio a Ciro Guerra

LA SOMBRA DEL CAMINANTE

di Ciro Guerra

Colombia - 2005 - 89 min.

(lingua: spagnolo / sottotitoli: inglese)

LOS VIAJES DEL VIENTO

di Ciro Guerra

Colombia / Argentina / Germania / Olanda - 2009 - 117 min.

(lingua: spagnolo / sottotitoli: italiano)

EL ABRAZO DE LA SERPIENTE

di Ciro Guerra

Colombia / Argentina / Venezuela - 2015 - 125 min.

(lingua: spagnolo / sottotitoli: inglese)

ABOUT CIRO GUERRA

Ciro guerra, a new master: unfinished meaning

In the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, the names of Rubén Mendoza and Ciro Guerra resounded in Colombia as advanced representatives of a new generation of filmmakers who, over time, have come to make up the new top echelon of national cinema, protected by the benefits of the Film Law, after a gap of years in which Lisandro Duque, Jorge Alí Triana, Víctor Gaviria or Sergio Cabrera had already prevailed as meritorious adventurers and, at the same time, marginal protagonists, as exiles, in a certain sense, of their own cinema. The nineties represented a trance in which the State refined concepts about the need for cinema while its departing management elites took the pulse of the new audiovisual realities in Colombia and the world, before fully operating on them according to orientations that were no less nationalistic and no less technocratic. Today, Colombian cinema has become more centralized than ever for the relative or doubtful but certain benefit of deciding to become official and grow, let's say, "grow big", which, undoubtedly, has been achieved.

Guerra, the slow titan

Ciro Guerra, comes from the coastal province, from Rio de Oro, in Cesar. He studied cinema at the National University but he had withdrawn to create, almost entirely on his own, at his own risk, and certainly under his own responsibility, his first feature film, in digital video. The search for accomplices, which was laborious and made by virtue of a presentable and growing, incessant work material, took effect, and La sombra del caminante (Guerra, 2004) before its release, got a legendary fame for the implications of such a gamble. The film, which performed woefully at the box office, fared much less poorly at festivals, and Guerra, who felt he had done more than well, abandoned his studies altogether and embarked on a new project that finally won him the opportunity to make the film of his dreams. Los viajes del viento (Guerra, 2009) received more publicity, was more successful, although not as much as its creators had hoped, traveled the world, was generally well commented on and left a great deal of concern about what would be the filmmaker's next craze.

It was Guerra's enormous, not to say excessive, ambitions what made him doubt about the success of the new feature film, because despite the phenomenon it was at the time, the very demanding experience of Los viajes del viento, in purely financial terms, was enough to ruin, for ever or for a while, the rise or continuity of the director as a talent spoiled by fortune. His idea was to continue a series of films about the regions of Colombia, as was the previous one about the northern coast, now in the Amazon, but the production cost what two or three normal feature films could be worth. Among other things, the difficulties of shooting in the jungle made the magnitude of the effort almost unfeasible, but Guerra once again found multiple backers and strategically, together with his lifelong partner, producer Cristina Gallego, produced an impeccable work that slowly, after an apotheosis premiere at Cannes, raised controversy and seduced national and international audiences, won awards and accolades at major festivals and right now([in early 2015) is nominated for the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film.

Now, all this is about a titan, but not yet about a master. It is true that in creators like Guerra, ability is already an objective professional value or, in better words, a value of artistic craft, if not of aesthetic order, if we speak in tune with more integrative (or realistic) conceptions of poetic work. But it is not enough to finish films, even if this means experiencing works as difficult to elaborate as those produced by Guerra and Gallego. There is something else in this duo that deserves to consider their creation with the utmost care, and in this, I bet, we are just beginning. We will insist that the colossal impetus, coupled with an almost exasperating perfectionism, has burnished a work of subtleties, and that with what has been done there is already a work worthy of an enduring and singular author, who in a certain sense is creating an inimitable and, more than personal, we would say that justly impersonal and transcendent cinema. I believe that Ciro Guerra still has the duty, already fulfilled but perhaps not yet concluded, to exalt his previous work. Let’s start from this. Let’s see how his latest feature film has elevated his previous cinema.

Guerra, an unique author

One of the lessons never learned, or unlearned, from Jorge Luis Borges, comes from his foundational story "Pierre Menard, author of Don Quixote" and has to do with the relativity of works of art. If post-structuralism inherited in part from such a lesson, which we will now try to enunciate, its acceptance of it is depressing by nature, because of the perpetual delirium it implies. On the other hand, a historicist vision of textual disciplines, and in fact any serious tendency to value or ponder the meaning of the intellectual production of human beings, can only strive to locate discourses, to find what is fixed or even unobjectionable in them. If I turn to this story by Borges, it is because the story is something, even if what it tells us is another story. In itself, Borges affirms that the works are very different at every moment, and in fact, by situating them, he slips them in time: any reading would be a falsification, a recreation. The height of objectivity would be the refusal of the work to be subjected, but this is its richness. Thus, Ciro Guerra's filmography has found a new face with Embrace of the Serpent (2014), and this is already unchangeable: a milestone.

What could seem vague and indiscernible, or sometimes quite the opposite, forced and bombastic, today is affirmed as a dignified and in process ceremonious style, equally allusive and imposing, and not because it loses its "clumsy" or "hesitant" character in La sombra del caminante, or because it ceases to be an abuse in Los viajes del viento, but because the naiveté of the former and the excesses of the latter are surprisingly linked, so that, in a new vision of both films, the unhingedness of Los viajes del viento shows an astonishing security, which frightens me, and the previous naiveté of La sombra del caminante stands as a prophetic intuition. Embrace of the Serpent is the film that modulates and unifies the dissonances of the two previous films, which as such were, in short, magnetisms, haughty idiosyncrasies, poetic endowments. No one could remain indifferent or deny the solvency of those films, but only now do they show so clearly their organic imbrication: the metaphors, the subjectivation, the turn towards a self-sufficient narration, the dynamics of dialogue, are guiding forces.

This article, which I began as a biographical sketch, slowly drifts towards a study, either cursory or thorough, of Ciro Guerra's films. I would like to focus on El abrazo de la serpiente, but I do not think it is possible, and I will dwell separately on his three feature films. Rather, the interest in that one, the third feature film by its author, will cross the entire text, since we are precisely seeing Guerra's work in the light of a new moment that releases anxieties of the mute or unconfessed and perhaps repressed stupor caused by his previous works. Guerra has never ceased to be a controversial character since his beginnings, and much of this is caused not only by the uncomfortably slow persuasion of his films on us, but also by the effect of that subtle and ambiguous persuasion on himself, who sees ratified at every step, almost unwittingly, or perhaps even created little by little, until sudden splendor, a unique way of being in cinema. Once I saw El abrazo de la serpiente, I told my brother Salvador Gallo that Guerra was a new master in Colombian cinema, and he, as always, did not understand anything. He just said: egg?

The subterranean allegory

It would seem necessary and perhaps misleading the correction that certain silence and ambiguity operate as recurring features in Guerra's last two films to understand that the difficult allegory of La sombra del caminante, that unlikely friendship of a victim of rural violence with his victimizer in the city, is not an imposed premise, not a trick or an ace up his sleeve, but an explanatory formula, a de facto vision, the conclusion of a process that gives a floor to his understanding, be it complete or illusory. Perhaps for those who do not take into account or have not seen the way Ignacio reads the message of master Guerra (the other master Guerra) at the end of Los viajes del viento, or the way Karamacate disappears in El abrazo de la serpiente, the final solution of La sombra del caminante is inevitably a sobering pose, an imposture. However, it is evident to me today that, from the beginning, the attraction that the film seeks to generate lies in the coexistence of rivals in the city, and in the fact that the unusual thing is that we do not see ourselves in any other way. We pretend urbanity in the cities, but we understand or know ourselves as enemies.

In other words, it is not possible or it would be insincere to argue that the allegory of La sombra del caminante, when Mañe and the silletero confess and we discover that the latter, who has gradually befriended the former, was the murderer of his family in southern Colombia, is not an almost complacent and very easy way out, but in the same sense it is tempting to propose it, it is difficult to deny it, as a hidden reality of our society, which if it does not come to light is because of the unseemliness of the tears. And this happens for two reasons: for the strength of the facts, and for the formal solutions of the film, clearly coded as a fable, as a story, rightly, allegorical from the start, or symbolic and even frankly oneiric. The two reasons add up to one, because what I call the strength of the facts is poured into the representation. When the silletero walks down the street at the beginning, there is a subjectification similar to the way Karamacate approaches Evan, at the end of Embrace of the Serpent, to blow not through his nose, but through ours. The silletero is overwhelmed by the city, and we feel the chaos through his eyes and his dulled perception.

La sombra del caminante, veering from crude video to an impossible black-and-white cinema, shows almost imperceptibly, but firmly, the twists and turns that will make Guerra's cinema a discourse that turns on itself. The assorted hallucinations when Mañe and the silletero drink from the plant's infusion and Mañe's simple but inspired dream, with the rain falling upwards (which involved a very sharp, back-to-front kind of filming), lead us to accept, well rather than badly, a correspondingly abysmal internal logic. This does not fit well not only with the logics with which the common citizen sees cinema, but also with those with which the critic must evaluate films in the mass and even specialized media. Guerra plays both sides, but its privilege is clearly defined, and the symbol of the plant, which is filmic reality, poetic eminence, healing link between pain and life, and between the other aggressor and the assaulted self, places the two characters as a spectator in front of a mirror. That is why the ending, when the silletero walks away (like Karamacate), frees Mañe with his own nature, and it is forceful.

The majesty of silence

A liberation such as the one intended by La sombra del caminante is problematic, but in the way that a sinner, a violator of the harmony of life, in the neutral words of the Bhagavad Gita, must accept and leave behind or transcend his guilt. This means that the murderer is not only an objective killer but operates in the film as blind evil, although I consider it inevitable to interpret the silletero as a victim of himself, even though we must understand this "self" as a form of social destiny, far from voluntarism or idealization of agency or atonement by an eventual divine or cosmic grace. The film is a dream, and this is not to speak lightly. This is how cinema works, especially in its realist aspects, and committing ourselves to this logic, instead of seeking a "politically perfect" work, led Guerra from failure with the public to the success of El abrazo de la serpiente. In the meantime, the filmmaker went through the construction of a portentous, incongruous but miraculously solid fable: the umbilical cord or Ariadne's thread that links daring with mastery: Los viajes del viento.

Now, I want to unify the meaning of the punctual, solitary tears of Mañe and Fermín, the boy apprenticed to master Ignacio in Los viajes del viento. I want to take further the idea, or the perception I have, that there is a notion of the world superior to allegory in La sombra del caminante, and thus the final note left by master Guerra to Ignacio in Los viajes del viento s is nothing more than the story of the silletero to Mañe: the confirmation of something that had not been noticed. We, the viewers, do not know what it says, and Ciro Guerra, director and screenwriter of the film, has sworn never to tell, but I already know. He says nothing. And he doesn't say anything because the film doesn't say anything. The silence in which Ignacio remains, an objective silence, is the assumption of a tradition, and when he begins to play the accordion in front of maestro Guerra's children, Fermín can only cry, because he has discovered something unexpected, which does not change anything, just like Mañe, but which gives meaning to everything. In this case, it is nothing more than a resigned silence in the face of that tradition which, at the same time, is that of the minstrel, an emissary.

Los viajes del viento, moreover, in the same way, is an autonomous work, which erases that minstrel and establishes itself on its own lyric, as if the devil were the one who made it in the way the accordion plays itself and condemns the minstrels to live that life. Supposedly, as Meyo tells Fermín, the devil is just a way of saying what tradition has conquered: the soul of the minstrels. They, wandering, fulfill the duty of carrying a story to which they cannot be unfaithful, and which is transmuted into a vision of the facts as if they were the same, or their essence, their spirit. At that point, the minstrels are the same reality told, in a diversity of tunes, sometimes very laconic, generally silent, perhaps. It is a step of a sad horse, a step of a tired donkey, a step of burden under the sun, or in front of a lonely plain, of women who leave each other in every town, of this vallenato very different from the one that the record companies would like to sell us since the seventies. Set in 1968, at the birth of the Festival de la Leyenda Vallenata, the film wants to be the apotheosis of a culture, and therefore denies a conclusion.

In El abrazo de la serpiente the illusion is forged in the same way, and therefore all historical ballast is just that: a deception, a referential anchor from which the protagonists themselves must free themselves, and ideally the spectator, whether a film critic or not, that is, in Luis Alberto Alvarez's terms, whether an intensive spectator or the ordinary spectator that Virginia Woolf might wish for (in analogy to her "ordinary reader"). All encyclopedism can work against this film, or be, on the contrary, the profitable path that we have all traveled in one way or another, as "jaguar writing", that enigma in which some Borges saw the word of God. That is why Evan and Kurtius are entities in which the biographical referents are emancipated, like doubles, like dream images, and that is why the essential question is whether we see, whether we are able to see the other. In the dream we consciously see an image of ourselves, which is the other. It is not at all necessary to turn to Freud either, the Amazonian and other ancestral cultures have told us this. We depend on our faculties to understand the dream as a living image.

Thus, El abrazo de la serpiente (and I will speak only for those who have seen it, without summaries) demands that we appreciate it on a wave opposite to the one Pedro Zuluaga or Marta Rodriguez ask for, according to their different but, in a certain sense, very close demands for "politically perfect" films. The film is a dreamlike encounter on principle, which implies a misencounter, an ambiguous passage of knowledge. Karamacate works as a projection of our longings and possibilities, even more so than Kurtius and Evan, who are instead collected and liberated, already in death, already in integrative plenitude, as the self of an aching spectator, dissociated in need and consciousness. Kurtius and Evan function and are, filmically, a mortal transmutation that allows Karamacate the return to himself, the possibility of being one, dissolving in the delivery of a knowledge. The relevance of this message is nothing but that of the victim, incarnated not in the Indian, but in the earth, in the jungle, in the message of a global body, in the non-genetic but spiritual information of a plant. Around it, Karamacate and "the other" are reborn, and are beyond this dual life.

Anointing with mystery

We are back to the beginning. Cinema is more like full life, or immaterial, because it experiences the reunion, the anointing with mystery. In Guerra's case, so far, the plant seems to be a motif not coincidentally integrating between his first, somewhat hesitant opera prima, and what constitutes his first legitimate masterpiece. The element of transcendence that in the desert can only be silence, and that governs everything, since before life, since before its embryo, as Karamacate reveals to Evan that it will be his dream, his inner journey to the beautiful contingency of the little drawings of light that we are, just little drawings. I want to remember Kafka here, I want to remember Kafka's Odradek, the concerns of the father of the family for that being that seemed to make sense but was unfinished, like a spool of broken thread. That is what we are. And the movies should be nothing but that. Our worry about whether we will be outlived is a sumptuary concern. Immortality is only guaranteed beyond our identity and our life. That is to say, this life is not the true life. The real life is all of it, more here, and that is what Ciro tells us, cinema as a dream.

Ciro Guerra's outstanding achievements as a filmmaker are beyond any doubt. It is enough to consider the subtle conception and filigree of the camera movements around the canoes in El abrazo de la serpiente to confirm the mastery he has achieved. In this paper we have tried to demonstrate that this aesthetic and discursive power is not improvised, but on the contrary, a long time elaboration, which undoubtedly began with his first visions of cinema, surely since childhood. We are in front of an author in the full sense of the word, a creator who imposes a seal on his work, and also a personal seal, of coherent thought and feeling, and who from my point of view has already crowned his work with a major work. No one can foresee what is to come, but we can assume that, as Luis Alberto Álvarez said in a personal conversation about Bertolucci, "it will always be interesting". It remains to be discussed his attentive work with the actors, a key issue in his cinema, and the way in which dialogue becomes a spiral vector that transforms his characters into a mutually enriching relationship.